Emerging public discourses around the COVID-19 crisis characterise it as unprecedented and disruptive. How exactly does this disruption affect masculinities? World over, the Coronavirus has been described as undoubtedly one of humanity’s biggest challenges in the 21st century. According to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, the COVID-19 pandemic is “a time of disruption that has brought grief to some, financial difficulties to many and enormous changes to the daily lives of us all.” In this reflection, I draw from my broader work on masculinities, supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Makerere University.

I focus on how the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted normative ways of being men in the context of global shutdown and self-isolation. Notably, self-isolation and the general stay-at-home campaign has challenged most of the everyday ways of being men — the evening conversations over a drink, sporting activities, and political gatherings among others — and meant that men and some women have had to ‘learn’ new ways of being.

COVID-19 Disruption in Uganda

On Wednesday 18th March 2020, President Yoweri Museveni ordered for the closure of all public events. Religious institutions, political gatherings and all schools, among other public engagements, were ordered to close shop at least for 21 days. Other measures followed gradually as the nation emphasised social distancing, staying home and washing hands regularly, way before Uganda registered its first COVID-19 case. These public health-centered adjustments, abrupt as they were (and still are), triggered shifts in men and women’s everyday ways of interaction.

Uganda and the mediated images of ‘men at home’

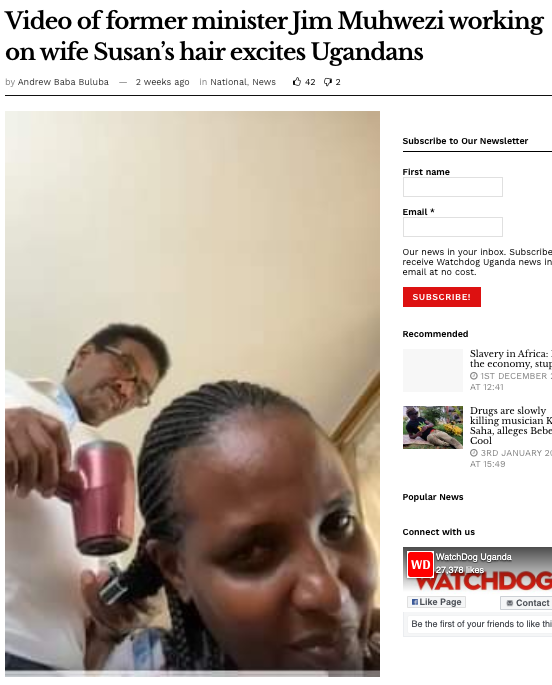

Perhaps you have encountered this sexist caution: “men at work!”. Well, majority of them are now at home! Popular reports about men’s experiences at home already point to anxieties and struggles as the majority of the male kin ‘learn’ to stay at home. In Uganda, social media is awash with visual and audio messages depicting ways in which men are struggling to cope with staying at home. Dominant images of young, middle-aged and older married men often packaged in cartoon caricatures and visual recorded short messages on social media alert us to the kinds of disruptions in traditional division of spaces (domestic vis-à-vis public) along with their attendant gender divisions of labour.

In a hilarious video that trended on the 6th April 2020, the public was treated to a one Hon. Kato Lubwama, who, purportedly speaking on behalf of middle class men, decried the difficulty men find staying at home. In a local dialect — Luganda, Hon. Lubwama exclaimed “Omusajja okubela awaka?! Awaka tewabelekeka” (meaning, ‘for a man to stay at home, it is extremely difficult’), before alerting us how he is coping by visiting the near-by public place even if there are no people to interact with. Other images depict men violently relating with their female kin, apparently upon misuse of money, receiving a phone call in secrecy among others. Yet, there are other men that have been ‘staying at home’ with or without COVID-19, those who cherish parenting and have afforded peaceable moments with their family members.

Source: watchdog.com (May 2020)

Ugandan experiences resonate with the rest of the world. For instance, nascent reports are beginning to reveal ‘surprising’ masculine vulnerabilities as statistics show higher numbers of adult men dying from the virus in relation to women across countries.

Moving beyond universal comparisons between male superiority and female vulnerabilities, COVID-19 has opened up a constructive conversation not only on possibilities of masculine vulnerability but also on multiple factors that intersect to shape femininities and masculinities. From Ewig Christina, a professor at the University of Minnesota, and viewpoints from the World Health Organisation, have elaborated on how masculine vulnerabilities in this crisis are potentially linked to certain culturally condoned ways of being an appropriate man. These include among others, smoking, alcohol drinking, inadequate health-seeking behaviours, and men’s likely reluctance to wash hands compared to women.

About the author

Amon Ashaba Mwiine is a GREAT Trainer based at the School of Women and Gender Studies, Makerere University.

For press inquiries or for more information, email us at great@cornell.edu.